When Meghan Rich, a sociology professor at the University of Scranton, first moved to Scranton, she sought the local music scene and a band her husband could join. “Basically,” she says, “the question was how to replicate our lives in Baltimore but on a smaller scale.” She found the area of downtown called “Scranhattan,” anchored by the bar The Bog (http://thebogscranton.com/) that hosted live music and drew a wider clientele than many neighborhood bars. Still, for many months Rich's husband couldn't find a band, or job, and neither he nor Rich felt particularly integrated into the city. “It's hard to break into Scranton life if you're not from here,” Rich explains. “It's a very tight community.”

Finally, a local musician needed a drummer. With the husband drumming if not fully employed, the couple began to make connections, as “any kind of arts community is more open than others.” That spurred Rich’s interest in researching the relationship between arts and community, and when she scratched the surface, she was surprised by the number of non-profits in the city that supported arts and culture.

Indeed, Scranton, like many other cities, has staked part of its vitality on arts and culture. The inspiration for that decision can be traced largely to Richard Florida, an urban theorist who argues that the “creative class” drives economic growth in an information economy and its members want fun places to live. Imagine stereotypical Apple employees–hip, young, and highly skilled engineers, consultants, designers, accountants, etc.–congregating in San Francisco or Boston. Fun equals their work but also entertainment and opportunities to meet each other, which means an arts and culture scene. In addition to attracting other industries and their employees, arts and culture can also be an industry in themselves — for instance, Broadway shows in New York or the museums and historical sites of Philadelphia. Many artists also become self-employed or start small businesses.

Undeniable Economic Impact

The organization Americans for the Arts regularly quantifies the business of arts and culture. Its next report is due out June 2012, but its previous report using 2005 data calculated the amount of money non-profit groups spent on arts and culture (hiring actors, producing festivals, etc.) and the amount of money people spent attending such events. In Pennsylvania, this arts and culture spending amounted to $2 billion, providing the equivalent of 62,000 full-time jobs and generating $283 million in local and state tax revenue. The average local attendee spent $20 beyond the cost of event admission and the average non-local $40.

Allegheny and Philadelphia Counties contributed the most to Pennsylvania’s arts and culture expenditures, while in Lackawanna County, which contains Scranton, organizations and audiences spent $17 million on arts and culture. Lackawanna County is unique in the state for its 1 mil property tax for arts and culture. Maureen McGuigan, Lackawanna's Deputy Director of Arts and Culture, believes people accept this tax because it supports museums, symphonies, festivals, programs for artists to work with the community or learn business skills, and so forth. “Do arts guarantee thousands and thousands of jobs?” asks McGuigan. “No. But it's all about creating a sense of place and quality of life which drives economic development. People are experiencing the arts, but they are also experiencing local community and are willing to invest in it.”

Jeff Parks, President of ArtsQuest in Bethlehem, makes a similar, three-part argument about the value of arts and culture to revitalize the city's former industrial core. “First, arts and culture is an industry.” One ArtsQuest endeavor, the 10-day Musikfest, alone contributes about $39 million to the community. “Second, arts and culture draw visitors. More people attend arts and culture annually than sporting events. Third, we're near the end of the transition from a manufacturing to a digital economy. Richard Florida's creative class, the people needed to reinvent businesses, pharmaceuticals, whatever, expect amenities. Arts and culture are a huge part of those amenities.” ArtsQuest built art studios in a former banana warehouse and performance venues on the former Bethlehem Steel site. Those projects in turn have crystallized other growth, such as restaurants and condominiums.

Other Ingredients Needed for Successful Recipe

Parks and Rich agree that arts and culture may bring people home if they also find jobs. Studying Scranton, Rich concludes “you just don't see people randomly wanting to move to Scranton. It's not Asheville. Arts and culture aren't necessarily attracting outsiders [to immigrate], but you are getting people from here who left and came back.” At the same time, Rich cautions that Florida's ideas haven't been well supported empirically, so cities need to beware, even if they are not wrong to deploy arts and culture as one approach to revitalization. After all, she asks, “What else are they supposed to do, curl up and die?”

Yet arts and culture, while supplying some jobs directly, does not supply them all. Rich's husband found a band but never a job, and the couple moved back to Baltimore. Rich now commutes to Scranton. “If you can't work,” she notes, “you can't live some place. You can have all the cool movie houses you want, but people need jobs.”

In Bethlehem, Parks has anecdotal evidence that “we're not just retaining some people, but attracting people who grew up here and came back and now say they could live here. Again, anecdotally, people who've been recruited by local businesses walk in the door of ArtsQuest and say, 'Thank goodness you're here. Now I think I could live here.'” For many struggling cities, that may be a necessary if not sufficient step: getting people who could work anywhere to want to live somewhere.

MARK MEIER is a writer, independent consultant, and part-time professor who lives in Dunmore and plants butterfly gardens in Scranton (which is his backyard). Send feedback here.

PHOTOS:

A large mural done by the community that represents transportation in Scranton hangs in Maureen McGuigan's office.

McGuigan works on arts and culture projects throughout Lackawanna County.

The Trolley Museum.

One of many trolleys you can step into in Scranton.

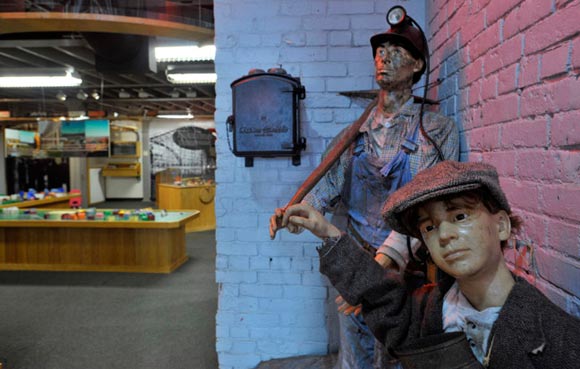

The Electric City and Steamtown are a large cultural draw.

Meghan Rich is a sociologist at the University of Scranton

All photographs by AIMEE DILGER