To get to the root of the Pittsburgh region's community development boom, you first have to know a little bit about the way the city operates — and sit tight, because it’s a bit complicated.

In Steel City, funding for improvement projects can come from taxes, private donors or from foundations. The same is true in boroughs.

The city of Pittsburgh is currently strapped for cash and under Act 47 receivership, as it has been for several years. Receivership empowers the state to provide for the restructuring of debt for distressed municipalities. It also limits the ability of said municipalities to obtain government funding.

According to Mayor Bill Peduto, that status acknowledges that the city has long under-invested in infrastructure and “must now begin more aggressively working to maintain its assets.”

“I won’t ask our residents to shoulder these burdens alone, while there is an opportunity for our nonprofit stakeholders to share in these necessary investments,” he said in a May statement.

This is one reason why you can’t throw a stone in Pittsburgh without hitting a community development corporation. If you’re not familiar with CDCs, you may wonder what they do. The answer, most likely, is everything and anything.

How a Community Development Corporation works

Some neighborhoods in Pittburgh have well-funded and well-established Community Development Corporations that were created because a group of concerned citizens wanted to effect positive change, explains Talia Piazza, program manager at Neighborhood Allies, an organization that funds community groups. She says that in most areas of the city, there are already groups of citizens working together on various projects.

Established CDCs are usually made up of board members who are stakeholders in the community — i.e. business owners, teachers or residents. They often have full-time staff who work in conjunction with the board members to devise a plan of action for the neighborhood.

In creating plans, they consult with other community groups, local residents, business owners and other parties at

public meetings. They then work to raise money to implement those plans.

Piazza notes that in Pittsburgh, CDCs have already done great things. For example, the Penn Avenue Arts Initiative helmed by the Bloomfield-Garfield Corporation and Friendship Development Associates encourages artists to access low-cost gallery space on the avenue and provides support for ongoing monthly open studio events, bringing many new visitors and invested residents to the area.

Thinking big on a small scale

While most CDCs work on a small-scale, there is no rule saying that things have to be that way. A group called Economic Development South is working on a broad scale to create overall improvement in the boroughs of Brentwood, Baldwin, Whitehall, Mt. Oliver, Pleasant Hills and Jefferson Hills, and the Pittsburgh neighborhoods of Carrick, Overbrook and Brookline.

“We are herding a lot of cats out here,” says EDS director Greg Jones. “Particularly when you layer in the fact that we are not doing just multi-municipality work, we are doing it with the school board and the business districts, and they aren’t always on the same page.”

Still, Jones says that in the three years his organization has existed, it has been able to get a lot accomplished. They are currently working with the Western PA Conservancy, 3 Rivers Wet Weather, the Office of County Executive Rich Fitzgerald, the Allegheny Conference on Community Development and Gateway Engineers on a comprehensive integrated storm water plan for the Saw Mill Run Watershed.

The watershed sits on land controlled by many different municipalities and often causes roadway flooding.

“Nobody was willing to step back and take that bigger perspective,” says Jones, explaining that EDS was able to meet with stakeholders and create a plan to move forward on the project. “Our communities out here are open minded because they’ve been trying everything else for 40 years and it hasn’t worked. Now by having all these groups willing to work on a regional scale, we’ve been able to do things that we couldn’t have done before.”

Getting involved

While you can start your own CDC and apply for funding for your next big idea, you may do best joining up with an existing neighborhood group, be it a church, a CDC or another non-profit, suggests Piazza.

If you join an existing group, your organization can then apply for grant funding for your project and you won’t personally have to go through the entire process of becoming a non-profit organization. You can also gather input from community members who may be able to improve upon your idea or suggest partners to work with.

Established community development groups may also have access to information that might be relevant to your project so that you can better make a case to funders, explains Piazza.

Creating a cool place to live

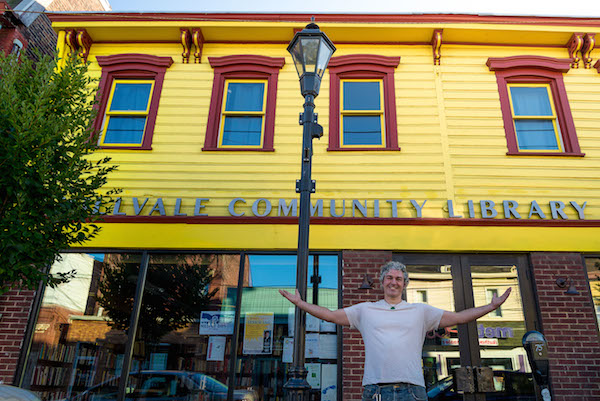

But what if you have the next big idea and the local CDC doesn’t want to work with you? This happened to Brian Wolovich, a teacher in Millvale.

In 2007, Wolovich and others wanted to build a library in the borough. They presented it to the Millvale Borough Development Corporation, but the idea was shot down.

“So we thought, let’s go to the Mayor and the council and surely that’s going to work,” recalls Wolovich. “We walked into that meeting and the same people running the development corporation were running local government.”

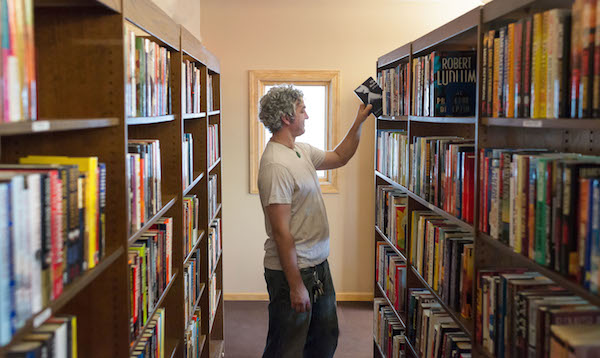

Years later, the library has been built and Wolovich is vice president of the borough council, but he says much re-electing needed to be done in order to prevent overlap and corruption. Also, he says it was initially difficult to get outside funding for the library project because funders were skeptical due to the lack of support from both elected officials and the development corporation.

However, despite the struggle, Wolovich sees what happened in Millvale as a success. His team turned funding difficulties into an opportunity to create a self-sustaining library, putting solar panels on its roof to provide electricity and renting out apartments on the property to generate revenue.

“We were building it with our bare hands, piece by piece, as money could be raised and as volunteers could make time,” says Wolovich. “We hope to be providing examples of how people need to not wait around. We are an example of what can happen with just rolling up your sleeves and getting to work. Our work can serve as an example for what can be done in other underfunded communities.”

Millvale is one of the areas Neighborhood Allies has decided to focus on for future investments. Other areas include Homewood, The Hill District and the Hilltop neighborhoods above the Southside, including Allentown, Knoxville and Larimer. Piazza says the group will also be looking to fund projects in Wilkinsburg.

“There are community based organizations, faith based organizations and different organizations that are doing work that has community impact and those are all people we view as serving communities,” says Piazza. “A lot of people, when they think about community development, they think about construction, but really it’s about creating a place where people want to live.”

This content is a collaboration between Pop City and Neighborhood Allies.