Henry Kissinger once said, “a diamond is a chunk of coal made good under pressure.” In Pennsylvania however, chunks of coal have always been diamonds. From the late 19th century, Pennsylvania anthracite built the railroads to the west, employed 300,000 miners and powered American industry through two world wars. To this day, Keystone-staters are standing on enough black diamonds to power Pennsylvania for the next 100 years.

Henry Kissinger once said, “a diamond is a chunk of coal made good under pressure.” In Pennsylvania however, chunks of coal have always been diamonds. From the late 19th century, Pennsylvania anthracite built the railroads to the west, employed 300,000 miners and powered American industry through two world wars. To this day, Keystone-staters are standing on enough black diamonds to power Pennsylvania for the next 100 years.

But in 2007, when Pennsylvania coal magnate John Rich attempted to bring coal into the 21st century with the nation’s first coal-to-diesel plant in Gilberton, he couldn’t raise the necessary funding. The project, which Rich says would have brought thousands of jobs and a clean use for the mountains of coal in Pennsylvania’s mines, was shelved just one year after being proposed, as Rich faced a lack of governmental support and mounting environmental concerns. Pennsylvanians were simply not buying the legend of clean coal. And today, it seems even more unlikely that coal will return to its heyday.

As energy standards begin to tighten, coal is slowly being placed on PA’s back burner. While the May 7th, 2009 Stimulus Overview paid lip service to researching clean coal technologies, the 7-point energy roadmap for Pennsylvania’s future funding omits coal completely. Despite providing 56 percent of Pennsylvania’s electricity, the White House and the State house have sent a very clear message to state coal producers: if you are going to keep producing and selling coal, you are going to do it without our help.

Nathan Willcox is the Energy and Clean Air advocate for PennEnvironment. His statewide advocacy and research group helped pen the official objection to the Gilberton project. PennEnvironment’s position–which has not been refuted–is that liquid coal produces nearly twice as much global warming pollution as regular gasoline. And while the Gilberton proposal contained methods for safely containing methane and other greenhouse gasses underground, these methods remain unproven on large-scale projects over the long term.

Nathan Willcox is the Energy and Clean Air advocate for PennEnvironment. His statewide advocacy and research group helped pen the official objection to the Gilberton project. PennEnvironment’s position–which has not been refuted–is that liquid coal produces nearly twice as much global warming pollution as regular gasoline. And while the Gilberton proposal contained methods for safely containing methane and other greenhouse gasses underground, these methods remain unproven on large-scale projects over the long term.

“We believe we shouldn’t put the cart before the horse, assuming that these capture technologies are going to work,” says Willcox. “Assuming that it did work, you would then have to look at the other environmental impacts of coal production. There are rivers in Pennsylvania that literally run orange from acid drainage of coal mines.”

According to the National Mining Association (http://www.nma.org/), there are 7,700 black diamond miners under Pennsylvania’s surface right now. And there are several thousand more in office and advocacy positions trying to save the coal industry for future generations. Groups like F.O.R.C.E. (Families Organized to Represent the Coal Economy) and the American Coal Council argue that Pennsylvania cannot afford to lose these jobs on technologies like wind and solar, that may take years to generate enough power to meet state demands. But several studies released since 2004 suggest that alternative energy provides more jobs over the long term. A 2006 study from Berkley, Calif, states that the U.S. could add 100,000 jobs by creating a fuel mix refocused on wind and biomass, leaving coal miners to retrain and join the new energy economy.

“The bills that have been proposed all contain a significant amount of money towards retraining,” Willcox says. “Because while no one is talking about shuttering all the coal-fired plants tomorrow, it is foolish to think that if we are really going to do something about global warming that the same number of people are going to be employed mining coal 50 years from now as are employed today.”

But what about all that coal? Hoping to complete John Rich’s vision of clean coal for the 21st century, mining companies like Consol Energy have chosen innovation over outrage, working on cleaner mines, cleaner fuels from coal and more safety in the handling of harmful greenhouse gasses. As the largest single owner of coal mines in the U.S., Consol has sought to modernize mining with ventilated methane abatement and is currently exploring alternate geological storage centers for CO2, like saline formations or unminable coal seams.

But what about all that coal? Hoping to complete John Rich’s vision of clean coal for the 21st century, mining companies like Consol Energy have chosen innovation over outrage, working on cleaner mines, cleaner fuels from coal and more safety in the handling of harmful greenhouse gasses. As the largest single owner of coal mines in the U.S., Consol has sought to modernize mining with ventilated methane abatement and is currently exploring alternate geological storage centers for CO2, like saline formations or unminable coal seams.

“We are monitoring the migration of this CO2, we are going to see if we get any leakage–so far we haven’t. If these efforts are successful, we can create near-zero impact coal power plants and get to wide-scale use in 15 years.” says Steve Winberg, VP of Research and Development for Consol. “If the country wants to get to that near-zero emission point, including CO2, we can do it.”

In the past year, Consol has partnered with the National Energy Technology Laboratory to monitor and demonstrate underground CO2 capture. Their efforts are part of a national project to demonstrate the safe sequestration of CO2 for its possible application towards clean coal technology. And while Pennsylvania has not set aside stimulus dollars specifically for coal projects, the National Energy Technology Laboratory will receive a piece of the $3.4 billion of national research grants the Office of Fossil Energy received last year.

Consol’s carbon sequestration efforts are just the tip of the iceberg for this emerging research field. In 2007, Ben Franklin Technology Partners invested $120,000 in an upstart out of State College called Carbon Trap Technologies. CTT’s research seeks to create not only a way of sequestering carbon and other greenhouse gasses from fossil fuel production but to make this process commercially viable for the average energy company.

Consol’s carbon sequestration efforts are just the tip of the iceberg for this emerging research field. In 2007, Ben Franklin Technology Partners invested $120,000 in an upstart out of State College called Carbon Trap Technologies. CTT’s research seeks to create not only a way of sequestering carbon and other greenhouse gasses from fossil fuel production but to make this process commercially viable for the average energy company.

Penn State University currently has a division of their Earth and Mineral Sciences Energy Institute working on extracting CO2 from fossil fuels. They call it the Clean Fuels and Catalysis program. Led by professor Chunshan Song, the CFC team is working on numerous projects to reduce the environmental impact of fossil fuel production. A porous, absorbent basket for extracting CO2 and creating coal-based liquid feedstocks top a list of active projects.

Coal, Winberg says, will outlive its usefulness by the turn of the next century. Until then, his company will continue projects that make use of the energy beneath our feet rather than pushing development of what he calls “inefficient sources” like wind and solar.

“The (environmental opposition) has blinders on.” Winberg says. “It will be years before alternative energy can take over for 150 years of coal infrastructure. You can’t push alternative energy technology faster just by throwing more money at it.”

The race is on to see who can win the battle for Pennsylvania’s clean energy future. As state utility rate caps expire at the end of next year, it will likely come down to cost, timeline and, of course, finding a diamond in the rough.

John Steele is a freelance writer and blogger in Philadelphia. He enjoys music snobbery, trash television and laughing at hipsters. Send feedback here.

To receive Keystone Edge free every week, click here.

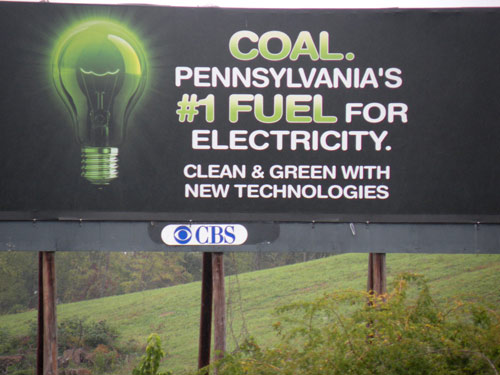

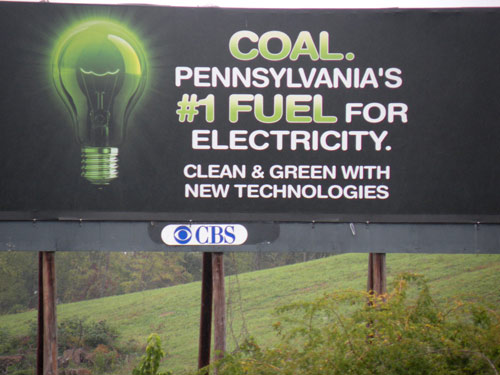

Photos:

Clean Coal billboard appearing all over Central PA (ecoscraps)

Nathan Wilcox (courtesy of Nathan Wilcox)

Steve Winberg (courtesy of CONSOL)