According to the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Pennsylvania has more rail-to-trail projects than any other state. Those 138 trails average about 10 miles each, but the state also hosts the first stretch of the longest multi-use trail in the country: the Great Allegheny Passage runs from Pittsburgh to Cumberland, Maryland, where it meets the C&O Towpath Trail to Washington, DC, for a total of 335 miles of person-powered travel.

As more trails are completed and planned, their economic benefits emerge. Beginning in 2006, various surveyors stopped people along Pennsylvania’s trails and asked how much they spent for the trip. Other times, postage-paid questionnaires were left at trailheads. Trail users’ spending was tallied in three categories: soft goods (such as food and drinks), durable goods (such as bikes and shoes), and overnight accommodations. Indirect benefits such as health and avoided pollution were not estimated.

Although it could be difficult to disentangle what portion of shoe sales, for instance, would have occurred without a trail, the surveys suggested trail users annually spent $130,000 to $28 million, as was the case with the latest study on the Lackawanna Heritage River Trail. A look at the LHRT exemplifies the benefits and challenges of multi-use trails.

An Important Regional Connection

The LHRT runs for 70 miles, through Scranton along the Lackawanna River to the Delaware and Hudson Rail Trail segment that leads to New York. The trail, partly under construction, will unify the Lackawanna Greenway, a region of spur trails and state and local parks and cultural sites. Ultimately, it will connect to the Susquehanna Greenway, creating a 250-mile loop through northeast Pennsylvania and southern New York.

The LHRT is administered by the Lackawanna Heritage Valley Authority, which celebrates its twentieth anniversary this September. Natalie Gelb, Executive Director of LHVA, cautions that the trail is important to LHVA but is not the only thing LHVA does. Technically a municipal authority of Lackawanna County, LHVA is a nexus for public-private partnerships. It tells the region’s story by facilitating collaborations and festivals, museum exhibitions, and other cultural events.

Gelb considers the LHRT “a linear interpretive park. Communities grew up along the river–coal, iron, railroads, manufacturing, textiles. It’s also an environmental story. The Lackawanna River was so polluted it was dangerous, but now we have trophy trout. It is an amazing example of reclamation.” But ultimately, says Gelb, “it’s really a story of the people. We celebrate the past but we don’t want to live in it. We want to bring new people with a new heritage.”

Trails help do that. Homebuyers and -sellers frequently cite trails as a valuable amenity. Local businesses also appreciate them. Zach Wentzel of Sickler’s Bike and Sport Shop in Clarks Summit observes, “Our number-one selling bike is a hybrid type bike which is perfect for the trail surface. Lots of people who want to start exercising specifically say they want to start riding the rail trail and ask for the bike for that.” Veronica Johns of Cedar Bicycle in Scranton concurs: “Customers come in and say they want to ride the trails. Lots of families out there want to ride together.” Both companies participated in LHVA’s Heritage Explorer Bike Tour in June 2011 as a way to support the trail and drum up business.

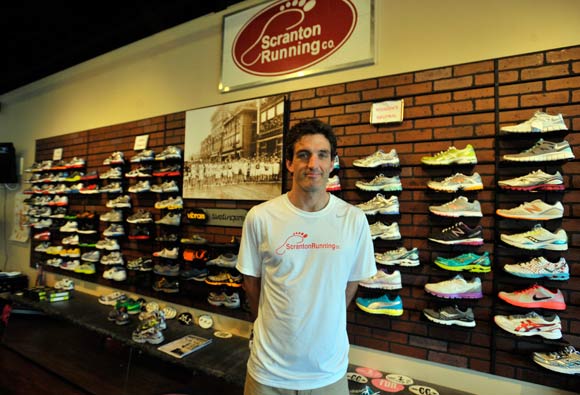

Meanwhile, Matt Byrne, a Scranton native and accomplished long-distance runner, founded Scranton Running Company in 2010. When considering where to set up shop, proximity to the trail was “definitely a selling point. We wanted to be in Scranton, not up in the malls, and it’s nice to be close to a gym. Four days a week we have scheduled runs that utilize the trail.” Byrne and others likewise volunteer to help LHVA maintain and advertise the trail.

A Job That’s Seemingly Never Finished

Despite the benefits, finishing the LHRT is rarely easy. Gelb compares the process to a crossword puzzle: you fill in the easiest parts first, you do another section, and suddenly, the pieces connect to complete the puzzle.

Closing gaps is also the state’s top goal. Diane Kripas, Chief of the Partnerships Division of the Bureau of Recreation and Conservation within the DCNR, explains why. “You get the greatest economic impact when you can create destination trails at least 50 miles or greater. People come for the trail, stay overnight, and bring economic benefits.” Moreover, communities benefit more when trails pass through, rather than skirt, them. Hence, there’s a push to improve signage for the trails and businesses alongside them as well as to bring rural trails into communities and to link communities. Most day-to-day users, Kripas says, “use trails more if they can access them from their garage. We need to have it fun and we need to have it easy.”

Kripas and Gelb agree on their two biggest obstacles: access and money. Often even a short stretch of trail can cross multiple municipalities and property owners, frequently railroads, some of which may still be active. “We need a 99-year easement for public use,” Gelb explains, to consider a site. There can be bridges, culverts, tunnels, utility lines, and other infrastructure to build or avoid. Then “there are environmental studies, engineering studies, you can’t be located in a flood plain, you need to make sure there’s no contamination, that the alignment works, and then you need funding to design and build.” All in all, the toll can reach $1 million per mile.

Funding often comes from PennDOT, the DCNR, and the National Park Service. LHVA solicited money from the National Scenic Byways Program for part of a trail near U.S. Route 6, the Governor Casey Scenic Byway.

If trails, however, can return millions annually in direct benefits, the money is well spent. “Companies look for quality of life,” Gelb remarks, “and then businesses crop up as a result.” Trails connect livability and commerce, personal and communal vitality.

MARK MEIER is a writer, independent consultant, and part-time professor who lives in Dunmore and plants butterfly gardens in Scranton (which is his back yard). Send feedback here.

PHOTOS:

Nancy Gelb stands next to a map of the Lackawanna River Heritage Trail and a community mural of the Heritage Trail

Matt Byrne, the owner of Scranton Running Co., has a location on Olive St. right next to a portion of the Lackawanna River Heritage Trail

Zach Wentzel aligns a bike wheel at Sicklers Bike Shop in Clarks Summit.

Gelb points out a section of the Lackawanna River Heritage Trail

Two young children walk down the Lackawanna River Heritage Trail in downtown Scranton, their parents not far behind

All photographs by AIMEE DILGER