Sergio Herrera learned how to make empanadas from his mother and grandmother. As he rolls out the dough and simmers the beef filling, he isn’t just preparing something to eat.

He’s thinking of family. When he gathers with friends, they’re remembering the traditions of their native Chile, whether shopping for groceries in the open-air market on Sundays or celebrating local holidays.

Herrera shared these stories in a video — while also teaching how to make empanadas — as part of a new project from Community Partnerships in Lewistown (Mifflin County) called Blue Juniata Foodways. Although food isn’t the first thing that might come to mind when thinking about the humanities, Community Partnerships is one of several organizations throughout the state using food as a way to bring people together, create space for isolated and neglected communities, and share history.

PA Humanities is helping to fund these programs through PA SHARP (Sustaining the Humanities Through the American Rescue Plan) grants.

“We really have found that food is something that connects everybody,” says Community Partnerships Executive Director Sam Price. “It can be a good way to build relationships between otherwise marginalized groups and get people to see the humanity in each other.”

For several years, the organization has worked with foodways and tradition-bearers who keep family and cultural practices alive. Combining the two was a natural fit. According to Price, it was especially important to reach the Spanish-speaking communities in Juniata and Mifflin Counties that may be overlooked or misunderstood because of the language barrier. For the project, each tradition-bearer films a video teaching how to make a dish while talking about the ways in which it’s used in their culture, family and history.

We really have found that food is something that connects everybody. It can be a good way to build relationships between otherwise marginalized groups and get people to see the humanity in each other.Sam Price

“We look at it as a way to approach diversity and approach anti-racism from a standpoint of sharing traditions and sharing food because it connects people,” explains Price. “People respond well to food because everybody eats.”

In the northeast corner of the state, nestled along the Delaware River in the town of Damascus, Farm Arts Collective marries food, theater, ecology and community engagement.

*This story is a companion piece to the podcast series “We Are Here,” created in partnership with PA Humanities. Learn more and listen now to the latest episode, which features an interview with Farm Arts Collective.*

Every year for the next ten years, they plan to create and stage an original production about climate change. This year’s piece is called “Tavern at the Edge of the World,” and is set in a tavern on the farm 40 years in the future. Performances take place on site, with audience members moving to fresh locations to view different scenes.

The creators hope the productions spark not only conversation but also action.

“I always say that if our audience walks away wanting to at least do something, or wanting to further their knowledge about climate change or wanting to take action or joining a group or doing something about it, I think that’s the goal,” says Company Manager Jess Beveridge.

As a working organic farm, Farm Arts Collective also hosts ecology and farm-based workshops taught by local experts, and have used that programming to explore issues of social justice, race and diversity. As artistic director Tannis Kowalchuk explains in the podcast, in an area that’s predominantly white, it’s important to actively work against racism and be engaged in topics surrounding social justice.

“I believe the arts and humanities is the only way forward in a world that is getting scarier and scarier,” she says. “Forget fear. Let’s get together and do something together. And that’s humanities. Making art and having conversations and working together and exploring issues together.”

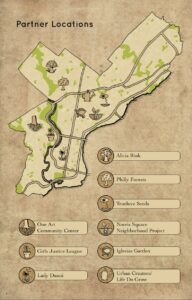

In Philadelphia, that connection between the humanities and food is underlined by the Painted Bride’s Resistance Garden. The program grew from a desire to examine and redefine people’s relationships with nature, farming, food politics, and the historical use of plants and herbs across different cultures. To do so, the Painted Bride, a performance space and gallery, has partnered with 10 organizations across the city that are working within the realm of nature, farming and food, and bringing art and artists to those spaces.

Forget fear. Let’s get together and do something together. And that’s humanities. Making art and having conversations and working together and exploring issues together.

“We initially thought, ‘Let’s make a garden,’” recalls Painted Bride Executive Director Laurel Raczka. “Then we thought, ‘Wait a minute — there are all these wonderful gardens all over the city, maybe we can just bring the arts to these programs that already exist to uplift them and bring visibility to them so people know about them.’”

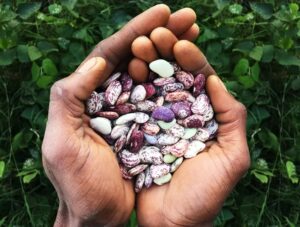

Partners include TrueLove Seeds, a farm-based seed company offering culturally significant, open-pollinated vegetable, herb, and flower seeds grown by more than 50 small-scale urban and rural farmers; The Urban Creators, an organization that uses food, art and education as tools to nurture resilience and self-determination in North Philadelphia; and Philly Forests, a small farm in Northwest Philadelphia with a mission to diversify the local food system.

To Raczka, resistance in this context means the ability for people to grow their own food and not be reliant on the corporate structures of grocery superstores or neighborhood markets that might not carry fresh food.

For project manager Amalia Colón-Nava, herself an artist and a farmer, it means autonomy of choice in terms of what people eat and who they rely on for food.

“I think it’s a radical act to be growing food, specifically for people of color,” she says. “It’s a radical act because it’s undoing a history, and continuing to fight against the oppressive systems that have made people averse to wanting to connect with the land. A lot of partner organizations we work with are prioritizing education around growing and why it’s important and getting kids excited about it. So that’s another element of resistance, too.”

The project includes artist residencies at partner sites, community potlucks at the conclusion of each residency, and four editions of a zine, Resistance Garden: Cultivating Abundance. The first issue explored land sovereignty and resistance, and featured submissions from partners on topics such as health and healing.

The Philly Forests growing space, where the Resistance Garden held its first potluck celebration, is located on the grounds of Awbury Arboretum, a 56-acre oasis where nature, history and community intersect. The arboretum received its own PA SHARP grant for a number of programs, including a Juneteenth celebratory meal. The sold-out program featured cuisine inspired by cooks of the Reconstruction Era and live performances from spoken word artists, poets, reenactors and musicians.

Back in Lewiston, Price plans for future Blue Juniata Foodways videos to spotlight Honduran pupusas, a Cantonese dish and a Ukrainian dish. The organizers also hope to work with members of the Plain Sect community, which includes the Amish and conservative Mennonites.

As for Herrera, his video has led to something more than sharing a recipe and insight into Chilean life. After so many people commented that they’d love to taste his empanadas, he offered them for sale during a First Friday event on August 5 at the bookstore where Community Partners shares space.

According to Price, Herrera was excited to be able to share himself and his culture with the community.

“Food is such a natural way to explore connections,” he says. “Two people who don’t speak the same language can be in a room and nod at each other like, ‘Yeah, this is good.’ Those little moments are what we really enjoy about this project.”

This story is part of the “We Are Here” series, which has been created in partnership with PA Humanities, an organization dedicated to building community and sparking change.

Funding for “We Are Here” comes from PA Humanities and its federal partner, the National Endowment for the Humanities, as part of the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021.

Lead image: Jess Beveridge and Tannis Kowalchuk of Farm Arts Collective